As the opening scenes scrolled across the screen, my first thought was that Anubhav Sinha’s drama was a period piece, but it didn’t take long to realise that the shocking events portrayed are straight out of today’s newspapers. The old-fashioned cars and equally archaic attitudes seem to be a blast from the past, but the reality is that the attitudes and events portrayed in the film are occurring every day, and not just in India either. The film follows new IPA officer Ayan Ranjan as he investigates the disappearance of three girls in a village in Uttar Pradesh. The police are disinterested, largely because the girls are from a lower caste and there is little incentive for them to solve the crime. On the contrary, once two of the girls are found hanging from a tree, there appears to be more gain in framing the girls’ fathers rather than risking their corrupt allies in a full-blown investigation. With an excellent cast, insightful dialogue and an uncomfortable and confronting storyline, Article 15 is a challenging depiction of the problems faced by a large number of people every day of their lives.

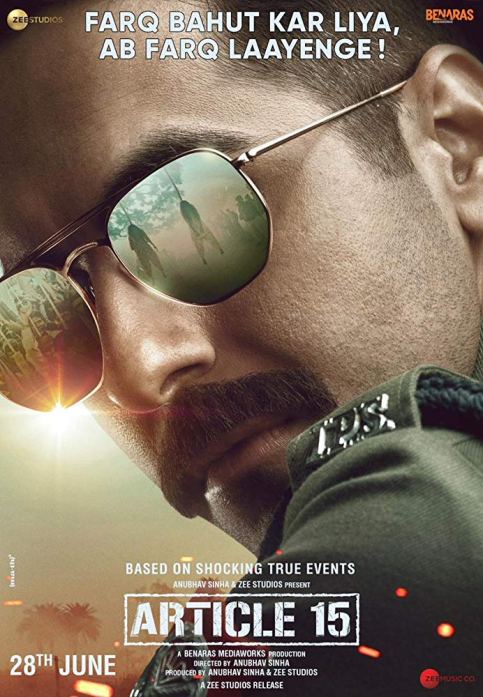

Ayan Ranjan (Ayushmann Khurrana) is a young IPA officer posted to Lalgaon in Uttar Pradesh, where he is taking over from the retiring long-term incumbent. The film opens with Ayan in his sleek car travelling smoothly towards Lalgaon while he chats on the phone to his girlfriend Aditi (Isha Talwar). He mentions the clean air and how beautiful the countryside is while his driver relates tales from folklore, but his arrival at the village quickly plunges Ayan back into real life. Outside of the cocoon of his car, Lalgaon is far outside Ayan’s previous experience. This is an area where Ayan’s privileged upbringing works against him, where he doesn’t understand the social hierarchy or how deeply local prejudice is entrenched, and where his principles that probably seemed so straight forward in the city, suddenly have to deal with the day-to-day reality of life in rural India. The soundtrack over Ayan’s arrival is Bob Dylan’s blowing in the wind – the words make sense once you realise that this experience will either be the making of Ayan, or it will leave him disillusioned and broken. Either way, he will understand what kind of a man he really is.

Ayan is at loggerheads with the senior police officer Bhramadatt (Manoj Pahwa) almost immediately as the police brush off the families of the missing girls. Gaura’s (Sayani Gupta) sister is one of those the missing and she is able to convince Ayan of the seriousness of the situation, explaining that the missing teenagers had gone to ask for a wage rise of 3 rupees. Ayan is sure that something sinister has happened, but he is hindered by his lack of understanding of the caste system and of how it affects everything in the small community. For him it’s simple: the girls are missing – register the case. But for the police who have to live in the community while senior officers come and go, it’s more about balancing the different factions and appeasing those who are willing and able to pay their bribes. The girls are simply too low in the social order to warrant any notice and worse still, their lives are considered disposable and therefore of no value. The situation gets worse when the bodies of two of the girls are found the next morning and the autopsy shows they had both been raped. Bhramadatt tries to intimidate the doctor (Ronjini Chakraborty) but Ayan gets to her first and manages to secure her support for an investigation which becomes ever more dangerous, eventually leading to Ayan’s suspension and own investigation by CBA officer Panikar (Nassar).

Ayan’s gradual realisation of the true consequences of casteism and the deeply ingrained prejudices is one of the key points of the film. He arrives in Lalgaon aware that issues of caste and inequality exist as abstract injustices that he has read about but which have never touched him personally. But being drawn into the hunt for the men who have raped and murdered the girls, leads Ayan to new realisations and opens his eyes to the hierarchical squabbles all around. Gaura provides Ayan with the information that he needs to begin to understand the deep social divide, while conversations with Jatav (Kumud Mishra), a police officer who himself is a Dalit, and Gaura’s partner, revolutionary leader Nishad (Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub), provide further insights. Nishad is the villagers champion, well-educated and articulate, but unable to gain any ground with the authorities dues to his low caste status. Jatav on the other hand believes in working with the system but is hampered by his colleagues’ inability to see past his low social status.

While Ayan conducts his investigation, events in the background echo real events and provide further evidence of prejudice and discrimination. One of the local politicians is attempting increase his supporter base and gain the Dalit vote by supporting a Brahmin-Dalit alliance. But there is no real benefit for the villagers in his proposed plans and Nishad and his supporters see the alliance as a betrayal of the community rights, leading to clashes and a Dalit strike. This gives one of the most memorable and effective scenes in the film that drives home the truly terrible working conditions for these people. As the strike takes hold the sewage in the police station starts to back up and overflow into the streets. As Ayan arrives one morning, there is a geyser of foul brown water fountaining up into the police yard, which resolves into a man surfacing from the drain with a load of the sewage material that has been blocking drainage. After dumping this he resubmerges. I just couldn’t believe that someone would have to do such a dangerous job without a protective suit, breathing apparatus and a safety line. Honestly, for me this is the most horrific and confronting scene in the film – even more shocking that the hanging bodies of the girls and the later revelations about their murder – mostly because no-one even seems to notice that this man is risking his life in such terrible conditions just to clean out a drain. With this one scene Anubhav Sinha seems to have captured everything that is wrong with the current system, and the murders are simply the extra dressing on the top.

What I like is that Ayan isn’t the all-conquering hero who storms in and solves the issue while the locals watch on dumb-founded. He makes mistakes and at times seems completely clueless about what is happening. It’s the local people who have the knowledge and impetus to find out what happened, Ayan just provides them with an authority to work under and a framework for the investigation. I also like that no-one is pictured as being all good or all bad, but simply as normal people who have their own share of faults (although perhaps Bhramadatt really is just evil!). With Article 15, Anubhav Sinha seems intent on educating his audience, pointing out just how the atrocities we read about can happen when human life is held so cheaply. But at the same time he’s not accusatory nor is he preaching, but rather simply pointing out what is, and then letting us judge these problems for ourselves. Ewan Mulligan’s excellent cinematography adds atmosphere and although Mangesh Dhakde’s background score is at times overly intrusive, for the most part the music is effective.

As someone who has only ever seen India’s caste system from the outside and who has no real understanding of the societal problems, this film is a real eye opener. The everyday situations I have seen when working in medical camps are explained so clearly here, and perhaps this film should be required viewing for anyone planning to travel to India. There is mysticism here along with the undeniable beauty of the countryside that sits uneasily beside filth, corruption and pollution. But the real triumph is in the depiction of the different characters who represent the broad spectrum of society and illustrate that there is some good and some bad in us all. A powerful and well-made film, Article 15 is not easy viewing but it is memorable and incredibly effective in getting its point across. Highly recommended for excellent performances and for shining a light on real social problems that have no easy answers.