Note – this review contains spoilers

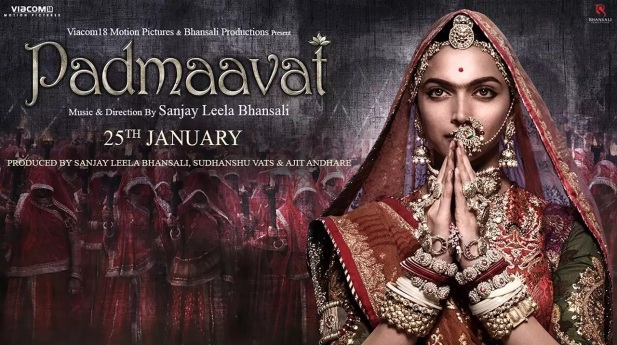

After all the hype, the protests and controversy, Padmaavat finally released in the cinema last week. And now that’s it’s actually here, it’s hard to see what all the fuss is about. With sumptuous costumes, lashings of sparkly jewellery, fantastical sets and very one-dimensional characters, the only possible way to describe Padmaavat is as a very expensive fairy tale. The main characters are all either very, very good, or very, very bad and there is no grey, no hint of any depth or any room to move outside the very strict boundaries of each persona. The film is based on a poem by Malik Muhammad Jayasi, so it’s obvious that Sanjay Leela Bhansali hasn’t set out to make a factual historical drama, and there are plenty of disclaimers at the start to drive home that point. And while there are some problems with the story, most particularly around the problematical ending of the film, it is exquisitely made, stunning to look at and a beautiful work of art. But it’s a work of art that has no soul and even with all the pomp and circumstance, ultimately Padmaavat ends up being surprisingly dull.

The story follows the exploits of two kings, Ratan Singh (Shahid Kapoor), the Rajput king of Mewar, and Alauddin Khilji (Ranveer Singh), ruler of Delhi. Ratan Singh is very, very good. He often wears white clothes, talks a lot about honour and Rajput bravery and is committed to following his rather strict principles. Alauddin Khilji is very, very bad. He murders his uncle to take the throne, sleeps with prostitutes on his wedding day and is generally portrayed as a rapacious monster, instantly ready for any kind of depravity. Ratan Singh is always very clean, Alauddin Khilji wears black and has dirt or blood smeared all over his face. There is no middle ground; these two are the quintessential opposites – the white king and the black king, pure good and pure evil – what else can Padmaavat be other than a fairy tale?

Ratan Singh meets Padmavati (Deepika Padukone) when he takes a trip to Sinhala to buy pearls for his first wife Nagmati (Anupriya Goenka). Padmavati is beautiful and clever, the white queen to Ratan Singh’s white king and although they meet when Padmavati mistakes Ratan Singh for a deer she is hunting and shoots him, they are instantly attracted to each other. The romance is stylised and extravagant. When Ratan Singh is recovering and getting ready to leave, Padmavati takes her dagger and slices open the wound, declaring that now he has to stay longer. But even with all this posturing, there is little chemistry between the two – smouldering looks aside there is very little substance to their relationship even after they are married and back in Mewar. Possibly it’s all the formality and ceremony that comes between them, the application of colours at Holi for example feels cold and ritualised rather than the usual spontaneous flurry of powder, but Ratan Singh’s Rajput pride seems a major barrier to any genuine relationship.

This is partly why Ranveer Singh’s Khilji makes more of an impression. Being totally evil, Khilji gets to do whatever he wants, whenever he wants with whoever he wants, and as a result is exuberantly happy, even when he is pining for Padmavati. A woman whom he has never seen, but still desires because he has to have everything that is unique in the world. Some of his excesses are so ridiculous that they are simply hilarious, such as spraying perfume on a female servant and then rubbing himself against her to transfer the scent.

Ranveer throws himself into the role with such passion and energy that of course by comparison Shahid’s Ratan Singh appears rigid and cold. He is, but the contrast between the two men makes the white seem insipid, while the black resonates with evil intensity.

While both men turn in excellent performances, Ranveer stands out for the sheer lunacy of his portrayal. Khilji is a monster, and Ranveer conveys his evil nature and total obsession while still managing to make the audience laugh. He brings everyone with him on his madcap ride into depravity and ensures that he is the central focus of any scene, no matter what else is actually happening around him.

Deepika Padukone has more to do since Padmavati has a fraction more depth than her husband. Think ivory rather than pure white. She’s also got more common sense than everyone else in the film put together, illustrated by her detailed plans and well thought out rescue of Ratan Singh after he is captured by Khilji. Of course, most of that could have been orchestrated by her two faithful generals, but Padmavati gets the chance to prove that she can fight and develop a plan of attack. Better than her husband to be honest, who bizarrely keeps believing Khilji will act with honour despite never seeing any indication that this will be the case. All of which makes it seem odd that Padmavati would commit all the women to jauhar rather than grab her trusty bow and arrow and die fighting. Regardless, Deepika Padukone looks stunning, even managing to rock a unibrow, and looks perfectly graceful and regal whether she is dancing for Ratan Singh, running through the forest or explaining her strategy to the generals.

A few of the peripheral characters also fare rather better. Jim Sarbh is excellent as Malik Kafur, Khilji’s assistant, general and sometime lover. Aditi Rao Hydari is also very good as Khilji’s first wife Mehrunisa and Raza Murad is excellent as Khilji’s uncle Jalaluddin.

However, Ranveer’s histrionics, the wonderful fabrics and stunning sets aren’t enough to disguise what is a rather lacklustre story. Every scene seems to be drawn out unbearably long to add yet more speeches about Rajput honour and bravery, or showcase beautifully designed costumes and breath-taking scenery that simply distract from the plot. It’s also predictable and that makes it somewhat dull, no matter how stunningly beautiful the film looks, or how ridiculous Khilji’s excesses become.

However, much of that is as expected for a Sanjay Leela Bhansali film – his attention to detail is amazing and every single scene is constructed as if it is a still-life painting with wonderful balance of light and shade, colour and depth. We expect extravagance, and that is what he delivers. What is more problematic though is the final scene where all the women commit jauhar rather than submit to Khilji’s victorious army. Despite the disclaimers at the start of the film, Bhansali seems to glorify the women’s march to the flames and adds many unnecessary details. It also goes on for a very long time so that the inappropriateness of the camera angles and discordant notes of the triumphant theme are emphasised. While the final act of jauhar may be true to the poem, and a historical reality of the time even if Padmavati herself is perhaps not, it doesn’t seem right that such actions should be seen as a ‘victory’ for the women and not a tragic loss of life. This is disturbing on many levels and while I don’t disagree with Bhansali’s addition of the final chapter to the story, I do feel that such celebration and exaltation is completely the wrong way to approach the subject. It’s a disturbing and jarring end to the film and simply doesn’t fit into the fairy-tale of the preceding two and a half hours.

Padmaavat is a stunningly beautiful film with much to enjoy in the sets and costumes. I could spend hours pausing this film on DVD and marvelling at the fabrics, the details in the palace floor tiles and even the plates and cutlery. Ranveer too is amazing despite his Khilji being such a one-dimensional construct and Padmavati is generally a strong female character. But the finale seems a direct contradiction to the disclaimer at the start while the story, for all its fantasy elements, never really comes alive. All of which makes Padmaavat a visual treat for anyone who enjoys the artistry of Bhansali films, but unfortunately not essential viewing for anyone else.

You’re right, it’s a fairy tale. And yes, Jauhar was a tragic loss of life. So was war. You’re talking of a patriarchy that enshrined valour and honour and ‘better to die than be dishonoured’ (for both men and women). You’re also talking of a future which, according to legend (and in reality), would have ended with the women triumphantly carted back with the victors, to be raped, abused as sex slaves, and perhaps sold to brothels afterwards. In the context of the story (and this is no way endorsing Jauhar or Sati – both of which I think are egregiously regressive customs), this is a choice that Padmini made for herself. To refuse Khilji the final victory of possessing her, or even getting a glimpse of her face.

And it’s a choice for the other Rajput women, as well (again, in the story). At different times, different women state that as their preferred option. To say, ‘Why couldn’t she marry the intruder and live a better life?’ (one of the criticisms levelled against the character), if you’re arguing ‘choice’, then you don’t get to choose for her. (General ‘you’.) Perhaps that would have been your choice; perhaps not. We can be very objective in a hypothetical situation.

I’m not arguing that rape victims should kill themselves because of the ‘dishonour’. I’m saying that if *I* were to see a future ahead of me that was filled with the prospect of being tied to a man/men against my will, to be raped over and over and over again, perhaps by more than one man, *I* would prefer death.

I have a great admiration for someone who endures that plight – the victims of the ISIS, for instance, who have endured and survived a brutal fate – but do you think those women had a choice but to endure? When ‘choice’ is not really a ‘choice’ and the only way out for you to live with yourself is death, should I apologise for choosing death over that life?

This, of course, is in the larger socio-context of the film. However, how do we film some of our legends and myths if today’s social context views them as regressive? From my land, we can never film the Ramayana, for instance, or even the Mahabharata. The legend of Kannagi, while it may be empowering from a feminist viewpoint, is something I find very problematic. She sets fire to an entire town, kiling everyone in it, except for the old, the very young – and Brahmins.

It’s a fine line to walk and I’m conflicted about opposing ideas of a film-maker having the freedom to film his vision of a subject, and a feminist who abhors the ideas that it shows.

And it is funny that a movie such as this needn’t have been a cause celebre if it hadn’t been for the political ambition of a party that no one knew about. I doubt this film would have been so controversial, or such a hit, if it hadn’t been for the acres of print and digital media given to chronicle the criticisms of the film, and spirited defences of it.

I watched it; I enjoyed the spectacle. At the end of the day, the film didn’t touch me, and it’s not something that will stay with me. But when the audience filed out, I found people discussing how horrifying they found the Jauhar scene. Despite the swelling background score.

(Sorry; I seem to have written an essay!)

LikeLike

Hi Anu,

I think it’s interesting that people in your cinema were discussing how horrifying the Jauhar scene was. I didn’t find it horrifying, but I was disturbed by the way it was depicted. As I said, I don’t have a problem with its inclusion, simply the way it was depicted as a ‘victory’. Death is sad and in my opinion shouldn’t be depicted as something glorious – and that was the overwhelming message I got from Deepika’s triumphant march towards the flames. I wanted to feel the emotion – any emotion, but it was strangely devoid of anything except how glorious they all looked. But that’s just the way it appeared to me. I wanted this scene to feel tragic, and appalling that they all chose to die – but I just didn’t. I totally get that death can be a valid choice, and it’s impossible to know who I would feel in that situation. Much as I would have preferred them to pick up swords and fight back, rationally I know that that is much more of a fairytale ending and also not the original story. It’s simply my preference and 99% of films don’t follow my ideas – if I want that I have to make my own film!

Also that when we’re talking about a legend it won’t fit into today’s societal norms, but there has to be some thought to how a message is conveyed. I was left unmoved by the tragedy – I kept thinking, ‘how far does Padmavati have to walk for God’s sake! How long is this going to go on for?” It seemed never-ending to the point of farce. That was my issue – not the deaths, not the concept – but the portrayal.

Like you I enjoyed the spectacle, and overall found it entertaining to watch. But it’s not the story or even the performances that I remember clearly, but rather the clothes and the sets. That wonderful jewellery! (and as I left the cinema THAT was what everyone was discussing – the amazing sets and the costumes!). I just wish SLB had added some depth and emotion – then it would have been a much more memorable film.

Cheers, Heather

LikeLike

‘how far does Padmavati have to walk for God’s sake! How long is this going to go on for?”

Heather, 🙂 Yes, that too. I’m quite sorry but in my mind, I was muttering, ‘Die already!’ I do think that, despite my feminist leanings, the deaths (or at least, their courage) were meant to be glorified. That an adored queen, renowned for her beauty, could destroy herself in such a way that the invader wouldn’t be able to possess even her corpse after death. (That, incidentally, was the reason for Jauhar – not just the deaths of the women who were therefore not abducted, raped, or killed in much more terrifying ways, but also the destruction of property so there would be nothing for the invader to pillage when he entered the city – it was the last act of defiance against an invading army.)

Yes, I could hear the gasps from the girl-gang seated behind me – young things – as the procession started. It was interesting to listen to their conversation afterwards while I was waiting for my ride. (I shamelessly eavesdropped.) The sets, costumes and jewellery were indeed beautiful – SLB pays a great deal of attention to the minute details. But while they fawned over that, their biggest takeaway seems to have been horror that women underwent such trials in those times. As I said, interesting.

As I said earlier, the film didn’t touch my emotional core much. I enjoyed it while it lasted.

LikeLike

I just don’t get the feminist criticism here. I read a news recently about yazidi girls(whom feminists won’t talk about, you know because that might instill islamophobia) choosing to get burned to death over being sex slaves to the captors. If you are saying they did that because patriarchy imbibed some kind of sense of honor in them, which compelled them to choose death over enslavement, I ask you how could you possibly know what’s going on in their heads? You and I can never understand the kind of horror they are going through. What if being a sex slave to some random person or people for life, is more horrific than a quick death? Is that a possibility? Don’t you guys talk about how women are objectified constantly? Then how can you not see that life of being nothing more than a sex object is no life at all? Where did patriarchy come in to picture, when you can deduce that from feminist language itself?

Also what’s wrong with celebrating what they did, when the only choice was between submitting to the vile rapists for life and committing suicide? Yes it is a tragedy, but I also think not giving what the captors wanted is a victory to the ladies. I can certainly respect that. It has nothing to do with honor being attached to their bodies.

I think you are conflating this case with the rape victims committing suicide out of shame. Nope. They are not the same.

LikeLike

I agree. These days it seems like they’re making way less of an effort to understand historical and sociocultural context and just analyze things at surface level from a Western feminist framework.

Events like this can be tragic and brave at the same time. If someone like Joan of Arc can be glorified for being burned at the stake against her own will, why not Rani Padmavati, who chose to end her life on her own terms? She died while maintaining the values she held dear.

And I’m not even getting into how important this tradition of death with dignity, or purification by fire has been to Hindu culture for millennia. Sita’s trial by fire in the Ramayanam, or Sati Devi’s death in the Daksha Yagnam or only 2 of the most influential examples.

LikeLike

Hi

I don’t understand how you think you would get anything other than a Western perspective from a blog that’s written in Australia from someone who is Australian! So no – I’m not going to discuss Hindu culture. I’m not Hindu and know just enough about it to realise that I know very little.

It’s tragic and the women are incredibly brave – but that’s not shown! You are talking about your reaction to this film – not what was actually depicted on screen. And that’s fine – we all have our own opinions, but you cannot tell me to understand from a historical and sociocultural context and then impose your views. I’m also going to disagree with Joan of Arc being glorified – she was canonised – not the same thing.

From what I understand about these concepts (and I’ve admitted that is not very much), it is understandable why someone would chose to die rather than be raped, tortured and killed. I don’t think you have to be Hindu to understand that! But I believe that it’s wrong to celebrate that. It’s a tragedy. Not a victory.

LikeLike

Hi dileep,

Interesting that you see this as feminist criticism. I would feel the same no matter who it was that was marching towards their death. – I really don’t believe that death should ever be celebrated. While I can empathise with the concept of ‘death rather than dishonour’ I don’t think that is a ‘victory’. As I’ve written, it’s not the inclusion of the scene that I had a problem with, but the portrayal. Defiance – sure, resolution – absolutely. But that’s not what I got from this scene.

The dreadful situations in many places in the world to-day have brought this much more to our attention. Africa, Myanmar, the Middle East – I cannot begin to imagine how I would react in those situations. I hope I never have to find out.

I would very much doubt that patriarchy is involved, but simply a desire to escape torture, rape and enslavement. But regardless, I don’t think that showing a mass suicide in a film is meant to be glorified. I think that this was a missed opportunity to show that horror and despair. Isn’t it terrible that people chose death by burning? Why do we let these things happen? What are we doing to stop this – and the rapes and murders that occur daily in our streets? This mass suicide should have made everyone talk about that – not how wonderful Deepika looked or about her ‘victory’. That’s just my opinion of course, but I wanted to feel some of that emotion with this scene – and it just wasn’t there.

Cheers, Heather

LikeLike

May be it’s just my desire to see that all is not lost, that the ladies did not die in vain and that the tyrant (who then went on to commit more atrocities) in the end left empty handed. I know I sound desperate, but I get your point.

LikeLike

I am Indian and Hindu. Jauhar is a historical fact. The problem is not with recording this or dramatising it but the it’s glorification. Deepika and the other women are dressed in bridal finery, there’s rousing music [very much like a victory at the end of a race/battle] and she takes thousands of women including children with her. The context /full perspective isn’t shown. It is not shown as a tragedy. She has to ask her husband’s permission to die. As a 8 year old ,my teacher narrated this story to a room of wide eyed impressionable girls in class [in a girls’ school] as an example of female honour,virtue and the unquestionable truth that it was better to die than be touched by a man other than your husband. It was very confusing to my innocent prepubescent self but as I started experiencing harassment in the streets and public spaces as a teenager in India the predominant emotion was embarrassment and shame. It was because of all the explicit and implicit messages from society about the female body .

This is the reason that Rani Padmavati is worshipped by some and why the Karni sena and others link the honour of the Rajput community and the royal household to her.The Karni sena tried so violently and reasonably successfully to stop the movie because of a rumour that their Rani was shown to be touched by the muslim barbarian in a dream song sequence . It is impossible to view this film, the surrounding controversy and the glorification of jauhar separate from the regressive patriarchal view of the female body and rape being attached to the pride of the husband,family and community . I agree with Dileep that some may have wanted to die rather than being raped or worse but you have to show the tragedies of history in context.

LikeLike

And someone quotes Sita’s trial by fire ! Another excellent example of a King’s [ Lord Rama ] honour being attached to his wife’s body .Sita is kidnapped forcibly by an evil king. Instead of seeing that the possibility that Ravana could have touched her against her will /raped her as a tragedy and gross injustice to Sita ,she is asked to prove her ‘virtue’ by jumping into fire. No wonder she left Rama and preferred living in a forest and raised her sons single handedly.

LikeLike